The history of Iran’s oil is inseparable from its contemporary history. Learning about oil may add to our knowledge of the country with a view to opening new horizons and paving the ground for further progress and development.

Oil and gas activities were so high in western Iran that in 2000 the West Oil and Gas Production Company (WOGPC) was established as an offshoot of National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) to specifically focus on that area. WOGPC runs five districts known as Naftshahr, Tang Bijar, Cheshmeh Khosh, Sarkan and Dehloran.

The Naftshahr production unit lies 220km west of Kermanshah and 60km from Qasr-e Shirin. It has a rated capacity of 15,000 b/d. The oil produced at the Naftshahr oil field is processed, sweetened and desalted prior to being pumped to the Kermanshah refinery as feedstock. Since Iran shares this reservoir with neighboring Iraq, it is a strategic and important oil field in western Iran.

The Tang Bijar production center is located 70 kilometers from the city of Ilam. The first phase of this center came online in 2007. It has capacity to process 7 mcm/d of gas. The gas gathered at this facility is sent to the Ilam gas refinery as feedstock. Gas condensate is also transferred to the Ilam refinery through a pipeline of 6-inch in diameter.

The Cheshmeh Khosh production unit is located 52km from the city of Dehloran in Ilam Province. It has a nominal capacity of 130,000 b/d (75,000 b/d of sweet oil and 55,000 salt oil). The oil produced at the Aban, Cheshmeh Khosh, Paydar, West Paydar and Dalpari is processed and sent via a 153-km pipeline to the Ahvaz production center and the Shahid Chamran pumping station.

The Dehloran production unit is located 20 kilometers southwest of the city of Dehloran. It has capacity to process 55,000 b/d of oil supplied by the Dehloran and Danan fields. A 52km pipeline will carry the processed oil to the Cheshmeh Khosh desalination unit.

The Sarkan production unit lies 15km from the city of Pol Dokhtar. It has capacity to process 30,000 b/d of oil that would be carried in a 21km pipeline to the Afrineh pumping station and finally the Kermanshah refinery.

Reynolds Indefatigable

Reynolds was scouring the entire western Iran, particularly Qasr-e Shirin, and verified reports provided by geologists appointed by William Knox D’Arcy. He visited fire temples in ruins in search of oil in the ancient traditions of Iranians. In Qasr-e Shirin, Reynolds visited Char Qapi Fire Temple. Charqapi is a historical monument of the Sassanid era in Qasr-e-Shirin. It was made of stone and gypsum and was counted as one of the largest fire temples of the Sassanid period. The fire temple has a square shaped chamber in the center with a domed ceiling, which closely resembles the other fire temples of the period. The width of the main opening of this fire temple is over 16m.

The main entry into the fire temple was located in the east, surrounded by spaces and a yard. The only surviving building in this monument is located in the westernmost part of the edifice. It was the most conserved part when Reynolds was visiting.

At a time when there was no seismography and geophysics available to verify underground oil and gas reserves, the only indicator for geologists to learn about hydrocarbon reserves was oil and gas gush.

Something strange kept Reynolds from conducting drilling around ancient fire temples. Furthermore, D’Arcy had to comply with the terms of the concession he had signed with Iran.

Article 4 of the concession read:

The Imperial Persian Government grants gratuitously to the Concessionaire all uncultivated lands belonging to the State, which the Concessionaire's engineers may deem necessary for the construction of the whole or any part of the abovementioned works. As for cultivated lands belonging to the State, the Concessionaire must purchase them at the fair and current price of the Province. The Government also grants to the Concessionaire the right of acquiring all and any other lands or buildings necessary for the said purpose, with the consent of the proprietors, on such conditions as may be arranged between him and them without their being allowed to make demands of a nature to surcharge the prices ordinarily current for lands situated in their respective localities. Holy places with all their dependencies within a radius of 200 Persian archines are formally excluded”.

Without this article, search for oil might have destroyed part of Iran’s history.

Adventure Begins

The name of Qasr-e Shirin in western Iran is intertwined with war and earthquake. However, not long ago, it was instrumental in Iran’s oil history; the period when Iran’s oil ended in the hand of D’Arcy and his colleagues and Reynolds started exploration. Reynolds was assured that oil existed in Iran’s territory.

Farshid Khodadadian writes: “In a strange link, the ancient monuments of the Iranian territory were directly linked with oil and gas resources in the country. If later on in May 1908, the first oil well in Iran and the Middle East became operational near an ancient fire temple in a Bakhtiari-dominated area, efforts got under way for oil exploration in Kermanshah and Qasr-e Shirin near a group of ancient monuments reminiscent of the Sassanid era.”

However, there is an older story of oil exploration in Kermanshahan Province in western Iran.

Khodadadian writes: “Many years before the signature of the D’Arcy Concession, by 1891, the then governor of Kermanshahan State had heard that there was oil and bitumen. He had asked French archeologist Jacques de Morgan to study this issue. De Morgan reported later that oil existed in Kermanshahan.”

The important thing with the start of drilling for exploration is that drillings in western Iran started by D’Arcy team around Qasr-e Shirin. Qasr-e Shirin is referred to in older books as Naftshahr.

According to Khodadadian, the surroundings of Qasr-e Shirin covered a zone sharing borders with the Ottoman government and extending as far away as the Naftshahr. Oil explorers had tried their chance for oil exploration in the area shared with the Ottoman empire before going to Zagros Mountains and the Bakhtiari-dominated area.

Differences emerged in the D’Arcy team. Some geologists did not believe in the existence of oil in western Iran, advising against the start of operations in the areas shared with the Ottoman empire. However, Reynolds remained adamant. Reynolds, who was an expert in drilling, came to Iran from London in 1901. He was determined to prospect for oil in western Iran. He had smelt oil in the ancient land.

Persian-Ottoman Territory

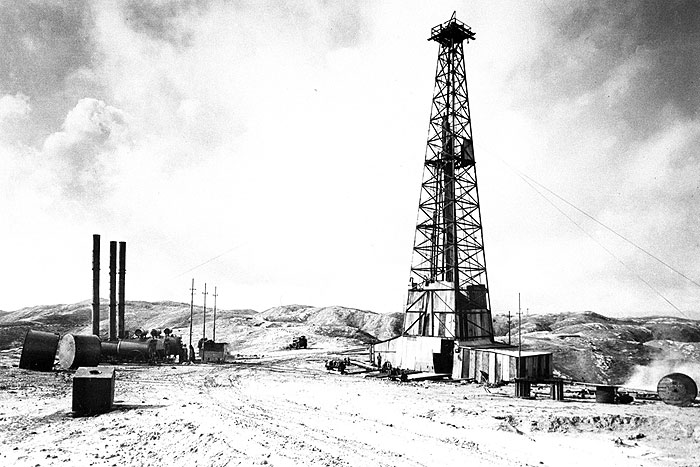

Restrictions incorporated in the contract pushed Reynolds towards Iran’s border area with Ottoman Khanaqin. The area was known as Chia Sorkh or red well. Drilling began there and Reynolds had to deliver necessary equipment by sea and through Basra in the Ottoman empire. There were so many problems and challenges in the way. On one hand, Reynolds had to go through very tough routes while on the other the Ottomans were not cooperative and did not let the equipment pass Khanaqin Bridge to reach Iran’s territory. Naturally, the Ottomans did not like their eastern neighbor to reach success in the oil sector. They finally started drilling in Chia Sorkh. But it did not last long because D’Arcy complained about no find. Reynolds’ dreams were shattered.

Khodadadian writes: “Anyway, the drilling of the first oil well began on November 8, 1902 in Chia Sorkh despite all local and political challenges. The oil rock was broken into pieces by drills and one year later, oil was seen at the depth of about 705 meters. However, the amount of oil was not sufficient to justify the continuation of drilling. Reynolds made a second attempt in Chia Sorkh near Well No. 1 and the oil extracted from the second well in January 1904 reached 120 b/d. Until this point, D’Arcy had lost about 150,000 liras of his initial investment and had told his friends that his money was limited.”

But news of oil discovery in Chia Sorkh pleased him and his friends in London. This happiness did not last long and turned into despair in May that year.

Drilling in Chia Sorkh cost Iran a lot as it drew the attention of the Ottomans. With political pressure and influence peddling, nine years later, i.e. 1913, the Persian and Ottoman borders were redrawn. Chia Sorkh was attached to the Ottoman empire. Following later partitioning, it is now part of Iraqi territory.

Courtesy of Iran Petroleum

Your Comment