The British were busy with Iran’s oil. But they were also looking at Iran’s political system. They knew quite well that to get their hands upon Iran’s oil permanently they had to know about Iran’s political situation and influential events.

Tehran was conquered and Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar had sought refuge in Russia. The post-constitutionalism years were coming and going without any positive change in Iran’s situation.

Everything was disturbed in Iran. As the Qajar dynasty collapsed, Constitutionalists failed to improve the conditions in the country. In the late 13th century AH on the solar calendar, Reza Mir-Panj, known for bullying, emerged in Iran’s politics. He led a coup in 1921 and became war minister. He promoted Seyed Ziauddin Tabatabei to the prime minister portfolio. Three months later, Tabatabei was dismissed to be replaced by Qavam al-Saltaneh.

Reza Khan was appointed prime minister in 1923 when Ahmad Shah, the weakest Qajar king, was in power. The weakness of this Qajar king facilitated the coming to power of Reza Khan to establish the Pahlavi dynasty. Emboldened by Teimour Tash, Ali Akbar Davar and Mohammad Ali Foroughi, Reza Khan spelled an end to the Qajar period. As soon as he ascended to the throne, Reza Shah was involved in oil issues.

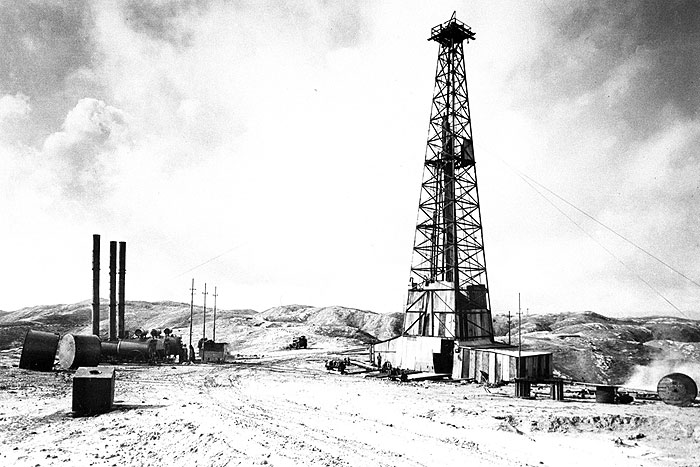

Emergence of Oil Issue

World War I was just over and the post-Qajar dynasty, i.e. Pahlavis, could stabilize their position. But the British needed more oil.

Mostafa Fateh and Araghi Zowqi in their books entitled: “Fifty Years of Iran’s Oil” and “Politico-Economic Aspects of Iran’s Oil” write: “In the aftermath of WWI and since 1920 onwards, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), recommended by its legal and financial advisors about the significance of oil reserves in southern Iran for the British government, decided to have the D’Arcy Concession renewed and settle the remaining financial and technical disputes. Britain’s dependence on Persian oil caused Iran’s oil production to increase from 1.743 million tonnes a year in 1921 to 7.087 million tonnes in 1933. However, Iran’s share of oil revenue did not increase as much Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC)’s income and was in some years even less than specified in the agreement. For instance, Iran’s royalties in 1931 were estimated at £872,000, while Iran had been paid £1.288 million a year before.”

That caused the British to undertake some serious economic steps in favor of their interests.

Benjamin Shwadran, in “The Middle East, Oil and the Great Powers”, explains that Sir John Cadman, Chairman of APOC traveled to Tehran in 1929 to start talks on the renewal of the D’Arcy Concession. He led a delegation to the Iranian capital and presented a series of proposals including the ceding of 20% of APOC’s shares to Iran, and renewal of the concession for 30 years.

During the talks, Iran had also its own demands, including 25% shares in the company and the right to be represented by two directors at APOC Board of Directors.

Iran also demanded minimum guarantee to have a share from oil revenue so that it would not see fluctuations in its oil income. Iran also wanted to have the company’s financial statement.

Britain ignored Iran’s demands. Pahlavi I, who owed his power to Britain, ordered newspapers to write in criticism of renewal of the D’Arcy Concession. The dictator had given green light, but he spoke of freedom of expression.

In his book entitled: “Power play: oil in the Middle East”, Leonard Mosley explains that Britain’s ignorance of Iranian demands pushed Reza Khan to order Iranian newspapers to be critical of the oil agreement.

Ali Dashti, an MP, spoke in opposition to the deal, calling on Iran’s then finance minister to reject the proposal for the renewal of the concession.

The British government had criticized the Iranian government for the newspapers’ articles; however, Iranian officials had claimed that newspapers were free in a bid to shirk from any responsibility.

D’Arcy Concession Set Afire

Pahlavi I realized that Britain ignored his demand. Therefore, he held a meeting and threw the D’Arcy Concession paper into a fireplace, describing this gesture as patriotic and honorable.

Mahmoud Pahlavi, in “Pahlavi Era Actors”, writes: “Negligence of demands formulated by Iran caused Reza Khan to throw the D’Arcy agreement into a fireplace and burn it away. At the order of Reza Khan, all newspapers wrote about this issue and tried to picture his act as a show of resistance to the British government. At the order of government, some festivities were even held in Iran and newspapers heaped scorn upon the Qajar dynasty for betrayal of Iran.”

Iran notified Britain of the annulment of the deal and the British government filed a complaint with the League of Nations. Iran’s representative to Geneva was Ali Akbar Davar who was summoned to justify Iran’s decision.

However, what was under way behind the scenes was totally different. Tolouei writes: “At that time, Iran was apparently insisting on its rights without any decision to step back. However, Taqizadeh has recounted in his memories that although Reza Khan had ordered Davar to go to Geneva, his behavior showed instability with regard to the continuation of hostility against APOC. Therefore, he ordered that a memorandum be signed with APOC very soon.”

Act of Patriotism

Widespread propaganda got under way and Pahlavi I sought to proclaim itself as savior of Iran’s oil and Iranians’ rights. But the fact of matter was totally different.

Nasser Farshad Gohar in “A Review of Iran Oil Contracts” writes: “Upon Reza Khan’s instruction, the 1933 Agreement was signed. The government and newspapers announced at that time that the agreement would grant Iran such concessions as limitations to APOC’s domain of activity, Iran’s increased share and the lifting of monopoly on pipelaying towards the Persian Gulf. In return, APOC agreed to pay up to £ 10,000 a year in funds for Iranian students traveling to Europe to study in petroleum engineering. The company had also to provide Iran with all necessary documents and maps. Despite Reza Khan’s efforts to show that this agreement had been achieved owing to his patriotism and perseverance against Britain, some aspects remained ambiguous. For instance, in the 1933 Agreement, APOC and its subsidiaries were beneficiating from customs and tax exemptions. The radius of APOC operations was limited; however, it managed to specify these sectors and choose areas with most oil. Also, despite the fact that the company had been granted the right to annul the agreement, Iran did not enjoy such right. Furthermore, the company had no obligation to exchange the money achieved from selling oil to Iranian currency.”

Fateh, for his part, has also offered an interesting analysis in his book: “Pahlavi I embarked on widespread campaign to show he is nationalist and anti-British and has managed to stand against Britain after a century of inaction with a view to restoring Iran’s rights. To that end, he engaged all his close confidants like Davar and Foroughi as well as official newspapers in the country. However, in a bid to pretend it was natural, the British government was also engaged to adopt a position in criticism of the government of Iran in order to harm an agreement with international significance. But the fact of matter was that everything had been arranged for the signature of the agreement to result in the longer presence of Britain in Iran.”

Mosley has pointed to one of the most significant reasons of the signature of the 1933 Agreement.

He has highlighted rivalry between the US and Britain over Iran’s oil, trying to portray Reza Khan’s patriotism designed to give legitimacy to his rule.

“One of the most significant causes of Britain’s signature of the oil agreement was its rivalry with the US since years ago on getting hand upon Middle East oil. Britain had convinced Reza Khan to renew the contract and therefore extend its foothold in Iran. However, arrangements had to be made for Reza Khan’s legitimacy not to be destabilized and the pillars of his rule would be solidified,” writes Mosley.

Oil Money for King

Apart from all these issues, one important point highlighted in history is that Iran’s oil revenue was deposited into Pahlavi I’s personal account. Such economic dictatorship shows that the Pahlavi rule was far away from the late Qajar dynasty’s constitutionalism period.

In his book entitled: “Reza Shah and Britain” Mohammad Qoli Majd writes: “There is documented evidence showing that of a total $155 million paid to Iran’s government in royalties, $100 million was paid directly to Reza Khan.”

A document whose authenticity has been proven shows that on August 25, 1932, a treasurer named Gauss Jason had confirmed money was paid to the king of Persia.

Courtesy of Iran Petroleum

Your Comment