Some researchers studying Iran's contemporary history maintain that the awarding of concessions to foreigners resulted from the act of treason by Mirza Hossein Khan Sepah-Salar among others. Some researchers believe that Sepah-Salar drove Iran into modern world following encouragement by the king for communications with overseas. Sepah-Salar who was first Iran's plenipotentiary ambassador to Istanbul was well aware of recovery from oil reservoirs all across the globe including in Iran's neighboring countries.

Sepah-Salar, who was considered an influential person in the Qajar history, was familiar enough with the secrets of European civilization and the progress of Occident.

Nasser ad-Din Shah first named Sepah-Salar his minister of justice, but due to his competence in promoting justice and reforming affairs, he was promoted to the post of chancellor.

Sepah-Salar believed that the best solution for salvaging Iran was to familiarize the country's top man with progress in the West. To that effect, he used to encourage the shah to travel to Europe. That was so that he arranged the shah's first trip to abroad in 1290 AH. During his stay, the shah got to know manifestations of modern civilization including oil recovery in Baku and other places. When he heard about oil recovery and he was said that petroleum existed in southern Iran he was persuaded to award the concession.

The awarding of concessions for exploitation of mines and resources in Iran had also opponents. Iran's northern neighbor was sensitive, but there were also patriotic Iranians who felt committed to safeguarding Iran and its progress. Seyed Jamaluddin Assadabadi was one of them. He developed the important theory of rule of law, constitutionalism and justice for Iranians. In his articles, he had warned against the consequences of awarding concessions to foreigners to exploit Iran's mines and he made public opinion sensitive to the disadvantages of dictatorial regime in power.

When in May 1896, Nasser ad-Din Shah was gunned down by Mirza Reza Kermani, a disciple of Seyed Jamal, at a holy shrine near Tehran, many years had passed since the failure of the first oil concession. These concessions had been noted indirectly in the nightly distributed leaflets distributed against Qajar rulers had started four years before and therefore the public opinion had become sensitive to them.

The 49-year reign of the Qajar king ended while Iran was becoming gradually familiar with the advantages of oil and gas recovery on its soil. In the meantime, Iran was hearing news about oil extraction in Burma and Baku. Muzaffar ad-Din Shah, who succeeded his assassinated father, was also informed of oil news.

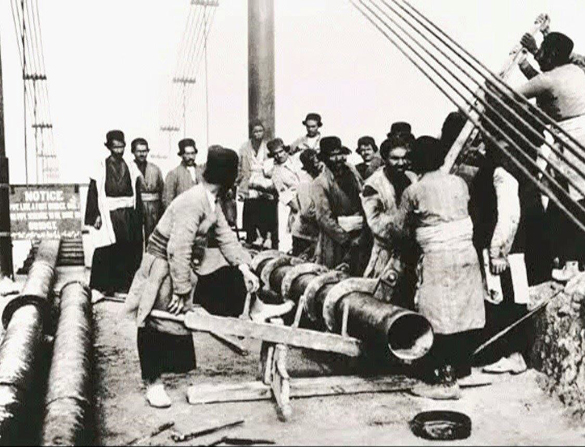

At that time, Iran was a pre-industrialized country and one of the most impoverished countries in the world. Its urban manpower was few and people were mainly working in traditional workshops. Workers were mainly daily paid. Unions were serving the interests of employers rather than those of laborers.

Muzaffar Shah came to power under such circumstances. He was the fourth son of his late father from Shokouh as-Saltaneh. When his father was killed he was based in Tabriz as heir to the throne under a Qajar tradition. Like his father, the new shah was very fond of travelling to Europe. He embarked on his Europe tour in April 1900. Many Qajar researchers believe that the Europe tour had been financed through giving customs outputs in northern Iran to Russia. Muzaffar's first visit to Europe lasted seven months. The fifth shah of Qajar visited Russia, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium and France. On his way back, he stopped over in the Ottoman country. During this visit, he was informed of the industrial use of oil, gas and bitumen and became more determined to exploit Iran's oil resources.

After Hutson failed in his attempt, Reuter decided to give a try to his chance for oil exploration in Iran. Reuter established a bank and purchased the shares of Hutson's company. Since exploration activities were limited to southern coasts, Reuter chose Qeshm Island for oil exploration, a 700-meter-deep well was drilled in Qeshm, but no oil was found. After this failure, the operation ended automatically. Everyone was frustrated with the failed oil exploration operation in Iran. Western investors and economic policymakers and Iranian leaders of the Qajar era were both perplexed. The latter was also grappling with serious financial restrictions. Despite all this, Muzaffar Shah was determined to retry his chance in turning oil into an epoch-making substance. While he was giving concessions to foreigners he eased security measures and suppression in the country. He opened the country to liberal newspapers like Habl ol-Matin and Parvaresh which were printed in Calcutta and Cairo. He lifted the ban on travel and named a new ambassador to Rome. Above all, he encouraged the formation of unions and education associations.

Sometime after, director of Iran's Customs Antoine Ketabchi (of Georgian or Armenian origin) was assigned the mission to travel abroad and find an investor for Iran's oil. Ketabchi was apparently supposed to inaugurate an exhibition in Paris, but his meetings and negotiations showed that his main task was to find someone who would be willing to invest in Iran's oil.

Ketabchi met Reuter’s former secretary whom he had got to know when Reuter was exploring in Iran. Ketabchi, the secretary and de Morgan met the British ambassador to Paris. The British ambassador had told them he knew a millionaire that could be of great help. The millionaire was William Knox D’Arcy.

Born in England in 1849, D’Arcy later immigrated to Australia and before investing in Iran’s oil, took the biggest risk of his life by purchasing an abandoned gold mine in Australia.

The mine was later found to have been full of gold. He became quite wealthy and was ready to use his wealth in another field. Therefore, he agreed to invest in Iranian oil exploration.

D’Arcy sent his secretary to Tehran in 1901 to study the terms and conditions for winning license to explore oil. His negotiations with the Shah of Iran paid off very soon. In the same year, D’Arcy was awarded the license for oil exploration in Iran. D’Arcy was allowed to explore, extract, process and export oil for 60 years on 480,000 square miles in southern Iran. The Iranian government was paid only 16 percent of the net revenues.

At the same time the Constitutional Movement was taking power in Iran.

Courtesy of Iran Petroleum

Your Comment